|

|

TODAY.AZ / Weird / Interesting

Happy birthday, airplane!

18 December 2013 [12:29] - TODAY.AZ

On December 17, 1903, Wilbur and Orville Wright took their famous first flight in Kitty Hawk, N.C. After four years of experimentation, the brothers became the first to fly a "heavier-than-air machine with a pilot on board." This article, which details the birth of the flying machine, was written by John McMahon for the September 1925 issue of Popular Science.

On December 17, 1903, Wilbur and Orville Wright took their famous first flight in Kitty Hawk, N.C. After four years of experimentation, the brothers became the first to fly a "heavier-than-air machine with a pilot on board." This article, which details the birth of the flying machine, was written by John McMahon for the September 1925 issue of Popular Science. When Orville Wright announced last spring that he would present to an English museum the pioneer airplane in which he and his brother Wilbur made historic flight on December 17, 1903, there was quite a stir in this country and abroad. President Coolidge hoped that the machine might be kept at home. There was promise of Congressional action, both to retain patent models in America and to investigate Mr. Wright's charge that the Langley relic in the National Museum at Washington had been refurbished improperly, manipulated and labeled to support a priority claim.

We can wait for Congress to clear up the Langley matter, which, after all, is a question of "might have" or "afterward also" rather than "did fly first." Meanwhile it is interesting to have a bit of light thrown on the yet obscure details of the "Wright brothers' independent and marvelous achievement. Their story, despite world-wide publicity, is still to be told. One reason for this is the death of Wilbur, the elder brother, in 1912.

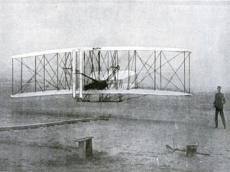

Orville piloting the flight at Kitty Hawk on December 17, 1903.

Popular Science archives

The young bicycle men of Dayton, Ohio, had been discussing the problem of flight for about three years when the first real idea came to them in June, 1899. They had spent Sundays lying on their backs beside the Miami River, hoping to learn something from the stately maneuvers of hawks and buzzards in the blue overhead. Then came that first real idea, which was Orville's—to obtain lateral balance by hinged wings.

"The hinge is a good idea, but not practical," agreed the brothers after debate. This was their judgment as expert mechanics.

The bicycle shop that the young men conducted was kept open late evenings to cater to the trade of factory employees. Wilbur was on duty one night in July, some weeks after the hinge concept had been argued and seemingly discarded.

A customer came in. If he had asked for tire tape, a wrench or a pump, the course of history might have been changed. But this customer asked for an inner tube for his bicycle tire. That tube was packed in a rectangular pasteboard box. Wilbur held the empty box by its ends while the customer examined the contents. Wilbur's hands were inclined to be nervously active. He looked down and suddenly realized what he was doing with an empty box—twisting it—warping it. What was this? Can't hinge wings? Never. But you can warp them! Eureka!

/Popsci/

URL: http://www.today.az/news/interesting/129242.html

Print version

Print version

Views: 2371

Connect with us. Get latest news and updates.

See Also

- 07 February 2026 [12:00]

Court allows Trump to detain immigrants without bond - 25 January 2026 [22:33]

Scientists solve 66 million-year-old mystery of how Earth’s greenhouse age ended - 20 January 2026 [14:34]

Spain train crash death toll rises to 41 after high-speed derailments - 19 February 2025 [22:20]

Visa and Mastercard can return to Russia, but with restrictions - 05 February 2025 [19:41]

Japan plans to negotiate with Trump to increase LNG imports from United States - 23 January 2025 [23:20]

Dubai once again named cleanest city in the world - 06 December 2024 [22:20]

Are scented candles harmful to health? - 23 November 2024 [14:11]

Magnitude 4.5 earthquake hits Azerbaijan's Lachin - 20 November 2024 [23:30]

Launch vehicle with prototype of Starship made its sixth test flight - 27 October 2024 [09:00]

Fuel prices expected to rise in Sweden

Most Popular

From Strasbourg to Epstein Files: How Jagland destroyed Norway's relations with Azerbaijan

From Strasbourg to Epstein Files: How Jagland destroyed Norway's relations with Azerbaijan

Pashinyan rejects calls to oust Russian military base from Armenia

Pashinyan rejects calls to oust Russian military base from Armenia

President Erdo?an praises security forces at Ramadan iftar in Be?tepe

President Erdo?an praises security forces at Ramadan iftar in Be?tepe

Events in Sumgayit: it was necessary for everyone except Azerbaijan

Events in Sumgayit: it was necessary for everyone except Azerbaijan

National Art Museum holds lecture dedicated to Khojaly Tragedy

National Art Museum holds lecture dedicated to Khojaly Tragedy

State Academic Opera and Ballet Theatre stages Christoph Gluck's production

State Academic Opera and Ballet Theatre stages Christoph Gluck's production

Turkiye unveils Samsun-Trabzon high-speed rail project cutting travel hours

Turkiye unveils Samsun-Trabzon high-speed rail project cutting travel hours