|

|

TODAY.AZ / Society

Russia Profile: "Moscow's Muslims defined by difference"

29 May 2006 [19:36] - TODAY.AZ

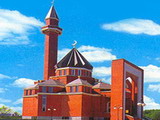

Otradnoye is an ordinary suburb of Moscow. After ascending the escalator from the metro, there's McDonalds, the Golden Babylon shopping center, and then, as far as the eye can see, gray identical twelve-story apartment blocks. Walk for 10 minutes along Khachaturyan Street, however, and there is a distinctly unusual sight for the Russian capital – a mosque. Two mosques, in fact, in a red brick building that is divided into three parts. The first part is the Yadryam Mosque, opened in 1997, the second an Azeri mosque, financed by the late president of Azerbaijan Heydar Aliyev and opened in 1999. The third part houses a rather incongruous beauty parlor, offering manicures and facials.

Nobody knows exactly how many Muslims there are in Moscow, largely because so many of them are semi-legal migrants (from the North Caucasus) or unregistered immigrants (from the South Caucasus and Central Asia), but unofficial estimates suggest the number may be as high as 2 million. And this huge congregation is served by just five mosques. As the home of two of these five, Otradnoye seemed like a good starting point for an investigation into the relatively hidden world of Islam in the Russian capital, and to see if the mood in the mosques was consistent with the moderate and integrationist rhetoric frequently heard from Islam’s public representatives in Russia.

"Come tomorrow. The head imam, Sheikh Mahmoud, will be happy to see you," a friendly female voice told me over the phone. Walking past the halal butchers and into the Yadryam mosque, Sheikh Mahmoud looked anything but happy to see me.

"Salaam Aleikum," he said suspiciously.

"Va-aleikum as-Salaam."

"Are you a Jew?"

Having ascertained a negative response, he began the discussion, quickly launching into a vitriolic diatribe about Israel, America and "so-called democracy". It was Thursday, and the mosque was empty except for a lady cleaning the entrance and a beautiful female voice chanting Koranic verses, wafting in faintly from a hidden room. "On Fridays, we're completely full. Tatars, Russians, Dagestanis, Chechens, Tajiks, Azerbaijanis – all kinds of people come here, and we all get along," said Mahmoud. "We teach people the true meaning of Islam – Islam is about peace and love, it's not about blowing yourself up." But when asked about radicalism at his mosque, he seemed to change his tune. "I am tired of people talking about radicals and extremists. These terms are constructions designed by the Americans and other governments to describe someone who disagrees with their worldview. Of course there are different currents in Islam, but we are all first and foremost Muslims; words like 'extremist' mean nothing," he said. "It reminds me of the early Soviet years, when people were accused of being 'whites', 'kulaks', 'wreckers' – it's meaningless."

But surely there are different interpretations of what is acceptable in the name of Islam – take, for example, Chechen warlord and self-proclaimed terrorist Shamil Basayev. "Well," said the sheik, "Basayev is a criminal according to Russian law. But for us, Russian law is not important. It is only Allah who can judge Basayev, he cannot be judged by the laws of 'democracy'. And it's not easy for Muslims to live in American-style democracy. Nor is it easy for us to live in Moscow. It is a corrupt city where everything is run by bribes and big business. If we don't have the money for bribes, we can't have land for more mosques. There are more than 7,000 mosques in Russia, and just five in Moscow."

Back in the center of town, just off Prospekt Mira in the shadow of the Olympic Stadium, is the Sobornaya Mosque, which opened in 1904. Although the Historical Mosque, built in 1813 to reward the Tatars living in Moscow for their contribution to the victory over Napoleon, is much older, the Sobornaya is the longest continually operating mosque. It was the only mosque that remained open throughout the Soviet period, reflecting the supposed religious freedom enshrined in the 1936 constitution.

On a normal day, the mosque is full, with the congregation mostly made up of elderly men, although there is a significant minority from younger generations who have dropped in for a quick lunchtime prayer, ranging from construction workers to sharp-suited businessmen. A marvelous cacophony of languages is spoken – mostly the Turkic sounds of Tatar, Uzbek and Azeri, but also the occasional Persian lilt of Tajik or the guttural Vainakh sounds of Chechen. The atmosphere seems more infused with casual socializing than religious zeal. "We just come here to relax, really," said one of a group of young Tajik construction workers, who preferred not to give his name. "It's one of the few places in the capital where we can find peace and quiet." Outside the mosque, a stand sold DVD of sermons as well as books, including "Polygamy Explained" and "The Laws of Islam Made Easy."

But the mosques are not necessarily the best places to try to gain an understanding of Islam in the capital. The very small number of mosques, as well as the fact that in the Soviet period most people did not have the chance to regularly attend prayer services, means that many Muslims prefer to practice their faith in private. Roza, 28, is a Tatar from Kazan who studied in the United States and Britain before returning to Moscow to work as a broadcast journalist. "I do believe in Allah and many things that the prophet – peace be upon him – preached," she said. "I also don't drink and don't eat pork. But I don't usually wear the hijab and I don't go to the mosque to pray. I haven't learned how to do the namaz [Islamic ritual prayer] and wouldn't know what to do – I would feel embarrassed."

Karim came to Moscow from Sierra Leone ten years ago to study. Due to the political situation there, he has been unable to return home and lives in Moscow as a refugee. "The last time I prayed in a mosque was 10 years ago," he said. When I was a student the university, authorities did not allow us to pray together, and now I do not feel safe being out on the streets. I practice my faith alone in Moscow and I think many other Africans do as well."

The most integrated of the Muslim communities in Moscow is the Tatar community. "There are around 700,000 Tatars in Moscow," said Nafigullah Ashirov, co-chairman of the Council of Muftis of Russia at a press conference. "We have been part of this city for hundreds of years, and have helped defend it from all kinds of enemies." But for all the integration, there is still a strong sense of Tatar identity, and there are still complaints. "For this number of people there is not one single Tatar school," said the Mufti. "This situation is amazing considering that Russian politicians are forever fighting for Russian rights in the Baltic states where there are thousands of Russian schools."

Roza agreed: "I want to know and learn more about my culture and my roots. I feel very sad that I don't speak my own language – due mostly, I think, to the Soviet policy of Russification." Despite the inability to speak Tatar, she still feels part of a strong community. "My Muslim identity is part of my cultural identity, and is part of being Tatar. I would never say that I have a Russian identity and this feeling has grown stronger as I got older. I do feel different and wouldn't want to be called a Russian!"

Over the last 10 years, the number of Muslims from the former Soviet republics and the North Caucasus coming to the capital has increased dramatically, changing the complexion of the capital's Muslim population. Part of the problem is that in Moscow, the issues of Islam and migration seem to be inextricably linked. The fact that Russian is rarely heard around the mosques is testament to the fact that national communities mostly stick together rather than mingling. Still, Heydar Djemal, the high-profile chairman of the Islamic Committee of Russia (a non-governmental organization) and often referred to as a spokesman for radical Islam, feels that there are the beginnings of a new Muslim consciousness developing that can unite the different groups. "It's true that before there was a big split. Fifteen years ago, there was not much in common between most of the Tatar community and people from the Caucasus, because Tatars are less passionate and less masculine," said Djemal. "They prefer to conform to power and were less radical and more afraid of confrontation. But Tatars are also changing. There is a new generation of Tatar youth who are as radical as the people from the North Caucasus, and the split is felt much less strongly."

But the migrants that the capital has found most difficult to absorb socially and psychologically are those from the South Caucasus and Central Asia. The migration issue came to a head late last year when the political party Rodina was banned from Moscow City Duma elections for advertisements featuring people who appeared to be of Caucasian origin, with an appeal to "Cleanse our city of garbage". While Rodina's ban was more likely due to political games than a genuine outrage at the racist message, the Moscow Duma is at least making some effort to combat the problems, setting up a new Committee on Interethnic and Interfaith Relations in February. "Given the feelings that exist in society, and the increased legal and illegal migration to Moscow, we need to work actively to ensure that tolerance and understanding is increased between different nationalities and faiths," said Igor Yeleferenko, the chairman of the committee. "If we don't do this, we can expect to see the kind of events that have been happening in Western Europe recently occur on the streets of Moscow."

Heydar Djemal, however, felt that violent clashes on the streets of Moscow are unlikely any time soon. "There is no 'white community' in Russia – it's just a lumpenproletariat. They might make isolated attacks, but there is no organization. In Russia almost all popular movements are stimulated and provoked from above," said Djemal.

A great number of the Muslim migrants work in Moscow's markets, which are often portrayed as being in the grip of migrant mafias. The implication is often that immigrants are becoming rich in the capital's markets while ethnic Russians are struggling to make ends meet. Nafigullah Ashirov strongly denied this. "These markets are not owned by Southerners at all. The Southern migrants buy a patch at these markets for a huge sum of money – and work day and night," said the Mufti. "I know many Muslims who work at the Cherkizovsky Market, and this place is the favored hangout of the Moscow police in the evenings. They turn up from all over Moscow to hassle people and extort money."

Kamil Kalandarov, head of the Al-Haq (Justice) Islamic organization and a member of the Public Chamber, agreed that life for the immigrants was hard. "When the Basmanny Market roof collapsed [in late February, killing 65, more than 40 of whom where Azerbaijani immigrants], we saw that there were many immigrants living there," said Kalandarov.

"It's like this in all the markets, on a scale that you can't understand. It's genuine slavery, with people living like dogs, or even worse." Ashirov, though proudly Tatar, feels he is very much a Muscovite, and as a Muscovite feels a strong sense of responsibility towards the capital's new arrivals. "I've lived here for years, raised my children here, and Tatars have been part of this city for centuries. But as Muscovites, if we can't guarantee these people basic rights, then we should be ashamed of ourselves. We should be ashamed to look these people in the face."

/www.russiaprofile.org/

URL: http://www.today.az/news/society/26664.html

Print version

Print version

Connect with us. Get latest news and updates.

See Also

- 12 February 2026 [15:36]

Azerbaijan to launch “mygov Business” digital platform for entrepreneurs - 12 February 2026 [14:29]

Opposition figures under investigation over alleged efforts to seize power in Azerbaijan - 12 February 2026 [12:58]

Slovakia, Azerbaijan sign major defense deal for SAM-120 self-propelled mortars - 11 February 2026 [14:07]

UAE’s Mohamed Ali Al Shorafa meets Baku officials, strengthens Azerbaijan-UAE ties - 11 February 2026 [11:02]

Azerbaijan’s Defense Industry Minister holds high-level talks at World Defence Show 2026 in Riyadh - 11 February 2026 [10:22]

Azerbaijan, US discuss modernization of healthcare system - 10 February 2026 [15:41]

Defense concludes in Ruben Vardanyan trial, final verdict pending - 10 February 2026 [13:46]

Georgia targets completion of key transit highway linking Türkiye, Azerbaijan, and Armenia - 10 February 2026 [13:03]

Azerbaijani FM meets US business delegation to advance strategic partnership - 10 February 2026 [12:27]

Baku Military Court hears case against Ruben Vardanyan

Most Popular

United States takes over nuclear security of South Caucasus

United States takes over nuclear security of South Caucasus

Baku and Washington have passed a verdict on the 907th Amendment

Baku and Washington have passed a verdict on the 907th Amendment

G-77 and China Group hold plenary at UNESCO under Azerbaijan's chairmanship

G-77 and China Group hold plenary at UNESCO under Azerbaijan's chairmanship

Defense concludes in Ruben Vardanyan trial, final verdict pending

Defense concludes in Ruben Vardanyan trial, final verdict pending

Israel's Herzog hopes US talks can topple Iran's 'evil empire'

Israel's Herzog hopes US talks can topple Iran's 'evil empire'

Reza Deghati's 'Rising Light' exhibition opens at Heydar Aliyev Int'l Airport

Reza Deghati's 'Rising Light' exhibition opens at Heydar Aliyev Int'l Airport

Georgia targets completion of key transit highway linking Türkiye, Azerbaijan, and Armenia

Georgia targets completion of key transit highway linking Türkiye, Azerbaijan, and Armenia