|

|

TODAY.AZ / Politics

Azerbaijan never demolished religious sites on its territory - Fuad Akhundov for Italian press

23 May 2025 [16:42] - TODAY.AZ

Armenian propagandists claim that certain objects—like plaques with fabricated Armenian names for occupied Azerbaijani cities and villages, or khachkars (stone crosses) commemorating soldiers and officers of the occupying Armenian army—should be considered "Christian heritage." But can anyone seriously believe that Azerbaijan should be expected to preserve and honor such a "heritage"?

This point is made in an article by political analyst Fuad Akhundov, published on the Italian online platform Informazione Cattolica.

Today.az shares an English translation of the article:

I read with great interest the letter by Mariam Ter-Ovannisian, a representative of the Armenian Council of Rome, published in your respected outlet. Ms. Ter-Ovannisian accuses Azerbaijan’s Ambassador to the Holy See, Ilgar Mukhtarov, of “distorting history.” Unfortunately, she makes several errors in her own arguments.

The formation of modern Armenia on historically Azerbaijani territory is a deeply tragic process—nothing like it happened elsewhere, especially in the 20th century.

This man-made tragedy began shortly after Russia resettled 100,000 Armenians from Qajar Iran and the Ottoman Empire to the region in 1828 (Glinka, S., Description of the Resettlement of the Adderbidjan Armenians into the Borders of Russia, Moscow, 1831, pp. 108, 114). This pivotal historical event, which reshaped the region, is something Armenians often prefer not to acknowledge.

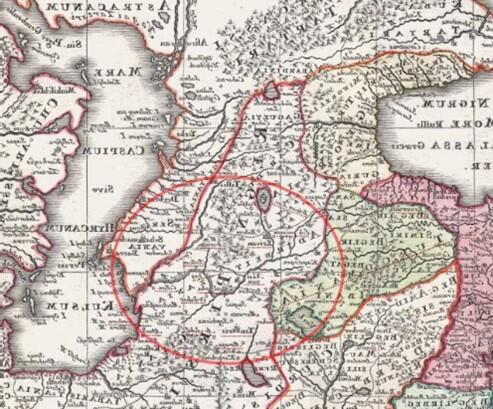

On European maps from that period, the South Caucasus is shown with Georgia and ten Azerbaijani khanates, often labeled collectively as "Azerbaijan" (e.g., maps by 18th-century German cartographer Georg Matthäus Seutter). There was no mention of Armenia—you can see this for yourself.

To understand the scale of the tragedy that followed the resettlement of Armenians to these lands in 1828, one only needs to look at how the architectural appearance of the Erivan Khanate— which became Armenia in 1918—changed afterwards.

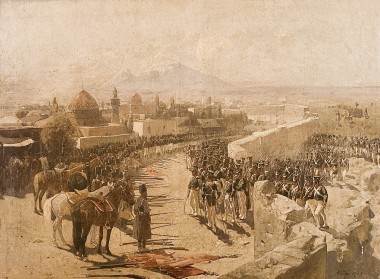

Compare, for example, the present-day central square of Armenia’s capital, Yerevan, with the accurate depiction of the same location in 1827 (the year Russian troops arrived) in the painting The Capture of the Erivan Fortress by the renowned Russian battle artist Franz Roubaud: https://roubaud.ru/sdacha-kreposti-erivani-1-oktyabrya-1827-goda.

Take a close look at this painting. Does it resemble a Christian Armenia? The Erivan Fortress depicted in the painting was built in 1511 by Azerbaijani ruler Revangulu Khan and was named “Irevan” in his honor. This is how the entire Erivan Khanate—today’s territory of Armenia - looked for centuries. It reflected the architecture of a typical Azerbaijani (Muslim) khanate, which was later destroyed to forcibly reshape it into Armenian (Christian) architecture - completely opposite in style. How could the historic center, a medieval fortress, have been bulldozed as recently as 1965? This was how traces of Azerbaijani culture were erased.

At the same time, the Azerbaijani population was expelled and subjected to genocide. According to the prominent Armenian scholar Zaven Korkodyan, in just two years between 1918 and 1920, 130,000 Azerbaijanis were killed and 240,000 were expelled. As a result, out of 373,582 Azerbaijanis living there in 1916, only 10,000 remained by 1920. That means 98% of the Azerbaijani population was killed or expelled. This genocide was documented not only by Korkodyan but also by Soviet journalist Anait Lalayan (Z. Korkodyan, The Population of Soviet Armenia from 1831 to 1931, in Armenian, Yerevan, 1932, p. 186; A.A. Lalayan, The Counterrevolutionary Role of the Dashnaktsutyun Party, in Historical Notes, ed. by Acad. B.D. Grekov, Vol. 2, USSR Academy of Sciences Publishing, 1938, pp. 100–104).

It is hard to imagine that Armenian President Levon Ter-Petrosyan - respected in the West - personally congratulated the Armenian people on the expulsion of Azerbaijanis, calling it a “centuries-old dream of the Armenians.” As a result, Armenia became the only monoethnic country in a region surrounded by four multiethnic states - Azerbaijan, Georgia, Iran, and Türkiye.

Simultaneously, under orders from Stalin and his successors, all Azerbaijani toponyms and hydronyms—around 2,000 in total—were renamed with Armenian alternatives. This information can be found in sources such as the Great Soviet Encyclopedia, where the historical Azerbaijani names and the dates of Stalin’s renaming decrees are indicated in parentheses next to the current Armenian names (see: https://www.booksite.ru/fulltext/1/001/008/100/487.htm and https://www.booksite.ru/fulltext/1/001/008/105/324.htm).

There is no other country in the world that has undergone such a dramatic transformation of its architectural, ethnic, and geographical identity in the 20th century.

It’s interesting that Mariam Ter-Ovannisian begins by questioning whether Christian heritage even exists in Azerbaijan—on the grounds that, in her view, Azerbaijan as a state was only established in 1918. But it’s unclear what evidence she bases that claim on. The tradition of statehood in the territory of present-day Azerbaijan dates back at least to the 3rd millennium BCE. Archaeologists and historians have clearly documented the region’s cultural and linguistic continuity. Even the name “Azerbaijan” has been known since the early centuries of the Common Era.

In fact, what first appeared in the South Caucasus in 1918 was not an Azerbaijani or Georgian state—both of which had long been recognized on European maps—but an Armenian state. While there were Armenian states before 1918, none of them were located in the Caucasus. In antiquity, Armenian kingdoms existed, but they were situated far from what is now modern-day Armenia. At a recent conference, I presented a ceiling fresco from a historic Vatican building, painted centuries ago, showing that the Armenia of that time was located far from Yerevan and the South Caucasus. Mass Armenian settlement in the area now known as the Republic of Armenia began only after the 1828 Treaty of Turkmenchay.

It’s also important to note that as soon as the three independent republics emerged in 1918, Armenia made territorial claims against both of its neighbors—Georgia (for Akhalkalaki and Borchali) and Azerbaijan (for Karabakh and Nakhchivan)—and launched military aggression. To this day, Armenia claims ancient Albanian churches in Azerbaijan and ancient Georgian churches in Georgia as Armenian heritage. There is a simmering territorial dispute with Georgia, but Armenia avoids escalation there—unlike with Azerbaijan, where it has framed the conflict as one between Christians and Muslims, a narrative that, regrettably, sometimes gains traction. But that framing doesn’t work with Georgia, another Christian country, and Yerevan knows it.

Given that context, it’s no surprise that Armenia accuses Azerbaijan of “destroying Christian heritage.” But let’s be clear: the author of the letter never specifies what “heritage” they’re referring to. Azerbaijan has never—never—deliberately destroyed churches or monasteries on its territory. The only exception was during the Soviet era, when the USSR’s anti-religious campaign led to the destruction of mosques, churches, and synagogues alike. Unfortunately, Armenian propaganda often labels things like plaques with made-up Armenian names for occupied Azerbaijani villages—or khachkars (cross-stones) erected to honor soldiers of the Armenian occupation army—as “Christian heritage.” Is Azerbaijan really expected to preserve that?

Here’s another example: In 1992, Armenia occupied the Azerbaijani city of Lachin. The entire population was forcibly expelled. In 1996, Armenian forces built a church on the site of the Ibragimov family’s destroyed home—using the very stones from their house. Is this the kind of “heritage” Azerbaijan is supposed to protect?

The most important point is this: respecting borders and territorial integrity is fundamental. When the Soviet Union collapsed, both Armenia and Azerbaijan were recognized within their 1991 borders. In Azerbaijan’s case, those borders include Karabakh. This means that Armenia’s presence in Karabakh was an act of aggression and occupation. Any structures built during the occupation are illegal and, by definition, cannot be considered “cultural heritage.”

Let’s also not forget that 20% of Azerbaijan’s territory was under Armenian occupation for decades. During that time, nearly one million Azerbaijani citizens were either killed or forced to flee their homes. An area of 10,000 square kilometers—roughly the size of Lebanon or four Luxembourgs—was completely devastated. Just look at what remains of the city of Aghdam. Occupied Karabakh became the site of one of the worst cases of urbicide in modern history. Nearly everything was destroyed: 64 out of 67 mosques, residential buildings, schools, hospitals, museums, galleries—even cemeteries and mausoleums.

No one has apologized. No one has been held accountable. The world looked the other way. And now, Azerbaijan is being criticized for not preserving plaques with invented Armenian names in towns that were illegally occupied?

Given all this, it’s more than a little ironic to hear moral lectures about preserving cultural heritage coming from the Armenian side. As for Ms. Ter-Ovannisian, we would respectfully suggest she revisit the principles of international humanitarian law.

URL: http://www.today.az/news/politics/259340.html

Print version

Print version

Views: 290

Connect with us. Get latest news and updates.

See Also

- 23 May 2025 [16:42]

Azerbaijan never demolished religious sites on its territory - Fuad Akhundov for Italian press - 23 May 2025 [12:18]

President: In the coming years, OTS can rise to even greater heights - 23 May 2025 [12:03]

Azerbaijan, Italy sign MoU on Naval Personnel Training - 23 May 2025 [11:13]

President Ilham Aliyev receives delegation of OTS Interior Ministers’ Second Summit - 23 May 2025 [11:11]

There are queues of conscripts in Armenia. For loans! - 23 May 2025 [10:44]

NATO Deputy Chief of Staff visits Azerbaijan to strengthen military cooperation - 23 May 2025 [10:10]

Did Macron bite Frank Schwabe? - 22 May 2025 [14:58]

Azerbaijan, Iran wrap up successful “Araz-2025” military drill - 22 May 2025 [14:43]

Trial of Armenian-origin individuals accused of war crimes continues in Baku - 22 May 2025 [13:39]

Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan plan stock market integration to boost participation

Most Popular

Corruption in Armenian: how Cash from Yerevan became the “voice of Europe”

Corruption in Armenian: how Cash from Yerevan became the “voice of Europe”

Azerbaijan expands industrial potential - investors invest billions

Azerbaijan expands industrial potential - investors invest billions

Durov went to war on Macron

Durov went to war on Macron

As peace nears between Baku and Yerevan, lobbying noise grows louder

As peace nears between Baku and Yerevan, lobbying noise grows louder

Azerbaijan, Iran wrap up successful “Araz-2025” military drill

Azerbaijan, Iran wrap up successful “Araz-2025” military drill

Israel's envoy praises Azerbaijan’s commitment to diplomatic safety

Israel's envoy praises Azerbaijan’s commitment to diplomatic safety

Carpet Museum to presents new project 'Knots of Time'

Carpet Museum to presents new project 'Knots of Time'